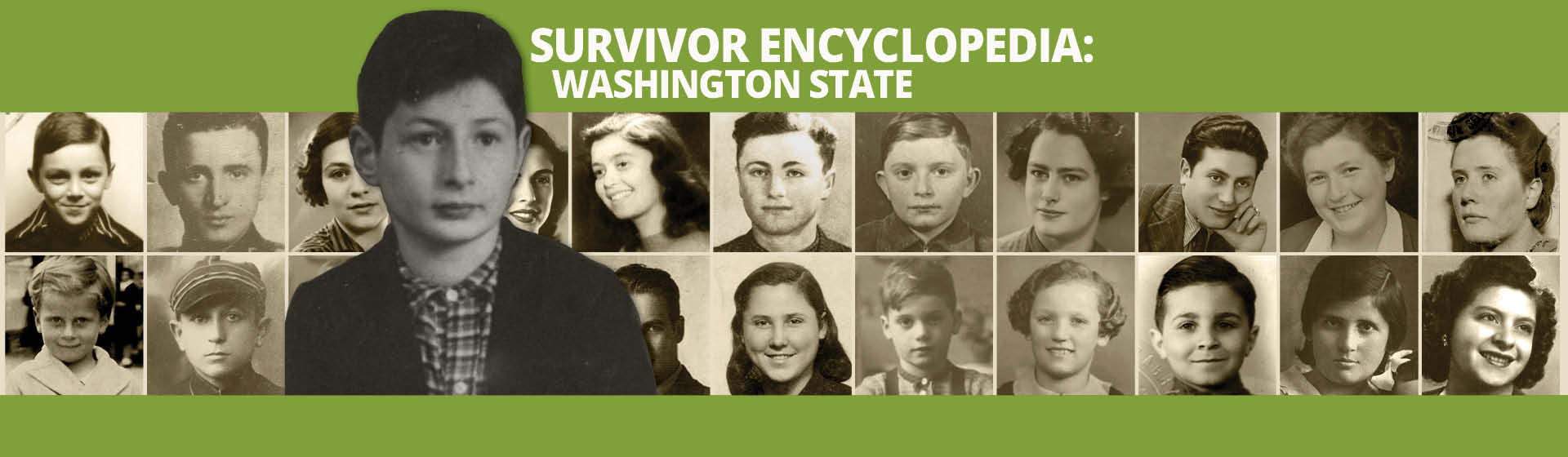

Granddaughter of Hungarian Auschwitz survivor Vera Frank Federman, Breeze Dahlberg shares her grandmother's story.

Izzy Darakhovskiy was born in 1936 and grew up in Yampol, Ukraine, then part of the Soviet Union. He was a young boy of five when the Germans invaded Ukraine in 1941. Not long after, Izzy and his family were forced to move to a ghetto in town. In September 1942, Jews from Yampol were rounded up and deported to a slave labor camp. Izzy and the other prisoners lived in primitive barracks made out of thin wood, with 35 people in one room. People were hungry and cold all the time, and the work never ceased. Izzy saw Nazis shoot and kill his own grandfather because he was unable to work.

Izzy Darakhovskiy was born in 1936 and grew up in Yampol, Ukraine, then part of the Soviet Union. He was a young boy of five when the Germans invaded Ukraine in 1941. Not long after, Izzy and his family were forced to move to a ghetto in town. In September 1942, Jews from Yampol were rounded up and deported to a slave labor camp. Izzy and the other prisoners lived in primitive barracks made out of thin wood, with 35 people in one room. People were hungry and cold all the time, and the work never ceased. Izzy saw Nazis shoot and kill his own grandfather because he was unable to work.

The camp was liberated by the Soviet Army in 1944. Izzy returned to Yampol, but the war continued for several months, and then a sever e famine made life very difficult. Izzy’s father returned from the front lines, but many, many men in the community had died or were seriously injured. Moreover, during this time antisemitism remained prevalent in the society and politics of the Soviet Union. The suffering of Jews during the Holocaust was not recognized, and Jews faced obstacles to go to school or get jobs.

Although Izzy went to school in Yampol, it lacked textbooks and even paper. Izzy loved to read and dreamed of being a teacher or doctor. Despite his high achievement and test scores, Izzy was not accepted at several choice universities. Instead, after being drafted into the Soviet Army for three years, Izzy was finally able to attend the State University in Moldova.

Izzy eventually completed two doctorate degrees and began a 28-year career as an economist with the prestigious Academy of Sciences in the Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, Izzy and his family immigrated to the United States the following year. They lived first in Rochester, New York, and since 2011 here in the Seattle area.

Izzy has been asked to lecture at the United Nations, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Woodrow Wilson Center , and other institutions. He has also written nine books, including a memoir and a book for children inspired by his granddaughters. Izzy is a current member of the Holocaust Center’s Speakers Bureau.

Matthew Erlich’s mother, Felicia Lewkowicz, was born in Krakow, Poland in 1923. Felicia was one of seven children, four girls and three boys.

Matthew Erlich’s mother, Felicia Lewkowicz, was born in Krakow, Poland in 1923. Felicia was one of seven children, four girls and three boys.

On March 3, 1941, the Nazis established the Krakow ghetto and Jews were required to wear armbands. Felicia and one brother were sent by the Nazis to the Krakow ghetto while her mother and other siblings were sent to Tarnow, 70 miles from Krakow. Conditions in the ghetto were terrible, with very little food and illness and diseases running rampant. Luckily, Felicia was able to get work outside the ghetto, cleaning the offices of German officers. One day, she did not return to the ghetto, escaping onto a train which would take her to Vienna, Austria. On the way, she stopped in Tarnow where she saw her family for the last time.

In Vienna, Felicia was able to acquire false identity papers and adopted the name Sophie Sterner. She worked at the Hess Hotel and the Hungarian King Hotel. Starting in the kitchen, she eventually worked her way up to housekeeping, assigned to the Hess family’s personal rooms. When a friend was caught smuggling clothes, a photo of Felicia was found among the clothes and she fled the hotel for fear of being caught.

Changing her name to Stephanie Heir, Felicia was able to find a position as a nanny and, later, at the Astoria Hotel. The authorities caught up with Felicia and she was sent to Auschwitz as a political prisoner.

Felici a arrived in Auschwitz in August of 1944 and was tattooed with the number A-25049. Shortly after her arrival, she was forced to give blood for German soldiers. To stop them from taking all her blood, a German nurse and fellow prisoner changed Felicia’s blood type on her records, and gave her bread and sausage to eat. Felicia attributes this act to helping her survive.

Felicia was transported with a group of 3,000 prisoners to Bergen-Belsen in October 1944. At the end of July 1944, there were 7,300 prisoners interned at Bergen-Belsen. By April 1945, this number had increased to 60,000. Overcrowding, poor sanitation, and lack of adequate food, water, and shelter led to an outbreak of disease. Tens of thousands perished in the first few months of 1945 and the bodies were often left in barracks for days before being removed. In March 1945, Felici a got Typhus. Her cousin, Estia, who she discovered on the transport to the camp with her, kept her alive by encouraging her to eat and get up.

Bergen-Belsen was liberated by the British on April 15, 1945. In May, Felicia and Estia were taken to a Displaced Persons (DP) camp in Lingen, Germany. In the camp, Felicia worked as a translator and met her future husband and fellow survivor, Arthur. After 6 or 7 months in the DP camp, Felicia moved to Paris, where her sister Lola was living, while Arthur completed his studies in England. Felicia and Arthur were married in England on July 3, 1948. They later moved to Canada and then the USA. The couple had four sons: Richard, Andrew, Michael, and Matthew.

In Memoriam: Holocaust Survivor Herbert Friedman. It is with sadness that we announce the passing of Holocaust survivor Herbert Friedman on October 1, 2020 in Maryland. He is survived by his wife, three sons, 7 grandchildren and 3 great-grandchildren. Herbert’s son, Ron Friedman is a Holocaust Center for Humanity Board member, Legacy Speaker, and longtime supporter.

If you would like to make a tribute in memory of Herbert Friedman please consider a gift to the Holocaust Center for Humanity. You can make a gift online here or send a check to Holocaust Center for Humanity, 2045 Second Ave. Seattle, WA 98121.

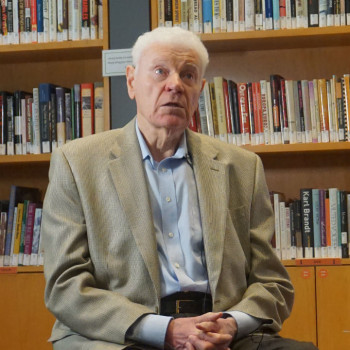

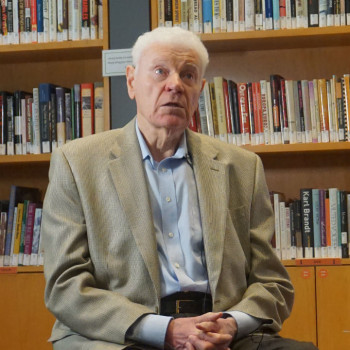

Ron Friedman is the son of Herbert Friedman, born in 1924 in Vienna, Austria.

“It is important to remember an event such as the Holocaust. It is a reminder to us all of the evils of bigotry and humiliation of others. Unfortunately, there are many holocausts in the world — both big and small — which have occurred since, and continue to occur. And it is left to ensuing generations to resonate the lessons of history.” – Ron Friedman

Herbert Friedman escaped from Vienna at age 14 aboard the Kindertransport. This event, and the ensuing years before Herbert’s emigration to America, were the defining moments of his life.

Herbert's family traveled from Radom, Poland to Vienna in the early 1920s. At the time, Jews played a central role in Viennese culture.

Herbert had a happy childhood. He attended public school during the day and Hebrew school at night. His mother stayed at home, and his father worked as a shoemaker. They lived in an apartment in a middle class neighborhood of Vienna and Herbert had many friends, Jewish and Christian. Herbert loved to swim, including in the Danube River in Vienna, known for its strong currents. At the age of 12, Herbert and another youth saved a young women from drowning in the Danube.

In March 1938, Austria fell under Nazi occupation and became part of the German Republic and the lives of all Jews came under threat. Herbert was immediately expelled from school by the Nazis, and Jews all over the region suffered. A particularly brutal act of anti-Jewish violence occurred in November 1938, Kristallnacht , when Jewish shops were smashed and looted, synagogues burned, Jewish businesses dissolved, and hundreds were arrested and taken away, never to be seen again.

Following Kristallnacht , Herbert knew there was no future life for the Jews of Vienna and he resolved at the age of 13 to escape. Through a series of unlikely events, Herbert was able was to meet an organizer of the short-lived Kindertransport (Childrens’ Trains) and to become a passenger on the first train of ten that left Vienna. The Kindertransport is credited with saving 10,000 children in Europe from facing a certain death in the gas chambers of Europe. Only 10 trains escaped before the Nazis ended the Kindertransport . Herbert was lucky to be among them. In the end, 1,500,000 children are estimated to have died in the Holocaust. Nine out of 10 of the children who were fortunate enough to have escaped on the “Kindertransport” never saw their parents again. Herbert took refuge in England throughout the war years, and was extremely lucky to have his family join him there before all immigrated to the U.S.

The pre-war years in Vienna and the Kindertransport were the defining moments of Herbert’s life. They affected him through courageous service in the U.S. Army in both WWII and the Korean War, raising a family, and successful career as a pharmacist.

Ron Friedman is now a second generation speaker and an attorney in Seattle.