Barbara is the daughter of Holocaust survivor Steve Adler. She assisted her father in telling his story , and after he passed away in 2019, Barbara decided to continue his legacy.

Barbara is the daughter of Holocaust survivor Steve Adler. She assisted her father in telling his story , and after he passed away in 2019, Barbara decided to continue his legacy.

Steve was born in Berlin, Germany in 1930, the younger son in a middle-class, Jewish family. In 1937, Steve’s mother, fearing for his safety due to anti-Jewish laws, enrolled Steve in a private Jewish school. The following year, the SS and Gestapo arrested more than 30,000 Jewish males during Kristallnacht. One of them was Steve’s own father Alfred. On November 10th, 1938, he was taken to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where he was held prisoner for six weeks before his release on December 23.

Conditions for Jews continued to deteriorate. In January 1939, the Nazi government required all Jews to carry identity cards revealing their heritage, and danger became much more immediate for the Adlers. That March, Steve’s parents sent him alone to Hamburg to join a Kindertransport (children’s transport) going to England by ship. Kindertransports were organized with British government sanction, giving refuge to approximately 10,000 Jewish children from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia – not their parents. Steve arrived in London knowing only one sentence in English. During the war’s intense bombings, Steve was evacuated to a small English town with his classmates.

Unlike most other Kindertransport children, Steve was reunited with both his parents. In spring of 1940, Steve’s brother Ralph and their mother Ilse met Steve in London. His father joined them in the fall, and they then traveled by ship for twelve days across the Atlantic, settling with relatives in Chicago.

After many years in Illinois and Connecticut, in 1999 Steve and his wife Judy, moved to Seattle to be near Barbara and her two children. Steve was an active and beloved member of Holocaust Center for Humanity Speakers Bureau for two decades.

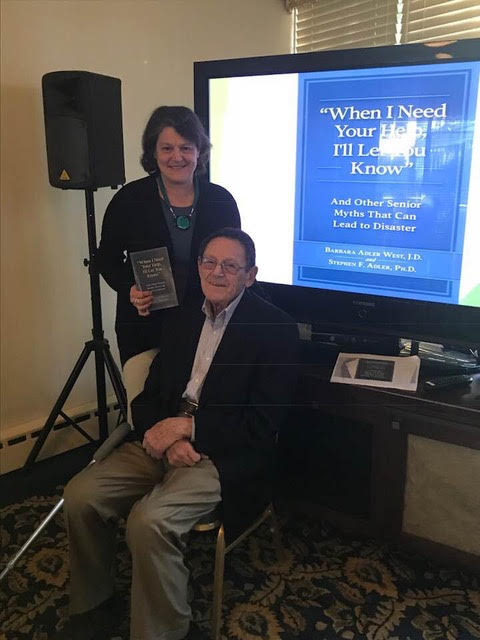

Barbara is an attorney, a mother, and recently started a non-profit organization to help folks in need with elder law. She is also the co-author, with Steve, of a 2017 book about families and aging, “When I Need Your Help I’ll Let You Know.” Barbara is very proud to share her father’s story as a Legacy Speaker in the Center’s Speakers Bureau.

Learn more about Barbara's father Steve Adler from his Survivor Encyclopedia page.

Clarice Wilsey, daughter of Army physici an Captain David Wilsey, M.D. who was one of 27 doctors who entered Dachau concentration camp at liberation, shares her father's story.

Dr. Wilsey was born in Wisconsin in 1914. After receiving his medical degree, he joined the military during World War II to serve as an Army physician. After serving in France and Germany, Dr. Wilsey arrived at Dachau in late April 1945. Prisoners were quarantined inside Dachau to wait for the allied commanders to see the atrocities, and to prevent the spread of deadly disease. The American physicians and medical staff risked their lives to bring healing to the 30,000 Dachau survivors.

Dr. Wilsey was born in Wisconsin in 1914. After receiving his medical degree, he joined the military during World War II to serve as an Army physician. After serving in France and Germany, Dr. Wilsey arrived at Dachau in late April 1945. Prisoners were quarantined inside Dachau to wait for the allied commanders to see the atrocities, and to prevent the spread of deadly disease. The American physicians and medical staff risked their lives to bring healing to the 30,000 Dachau survivors.

Dr. Wilsey’s family knew very little about his wartime experience. In 2009, when his children were cleaning out the family home, they found for the first time a box of letters Dr. Wilsey had written to his wife Emily while serving in the military, including the Battle of the Bulge and Dachau. The letters had survived several moves and even a house fire. Dr. Wilsey asked his wife in several letters “to tell thousands so that millions will know what Dachau is and never forget the name of Dachau.” His daughter, Clarice, was deeply affected by the discovery of the letters. She believes that her calling is to speak the words he was unable to voice after the war.

Clarice Wilsey, M.A., was a university faculty member and administrator for 45 years. She is now retired to spend more time reminding audiences to “never forget ,” and is a member of the Holocaust Center for Humanity Speakers Bureau. In early 2020 Clarice and co-author Bob Welch published a memoir, Letters from Dachau: A Father's Witness of War, a Daughter's Dream of Peace. Find and order the book from Barnes and Noble or Amazon.

The collection of Dr. Wilsey’s 280+ letters and other materials are preserved at the Holocaust Center, and will be used in future exhibitions and for educational purposes.

Born in Aschaffenburg, Germany in 1928, Charlotte was the youngest daughter of Fritz and Lucie Levy. Her family belonged to the local Jewish congregation where her father, a menswear salesman and World War I veteran, was the treasurer. Charlotte remembers having a happy childhood.

Born in Aschaffenburg, Germany in 1928, Charlotte was the youngest daughter of Fritz and Lucie Levy. Her family belonged to the local Jewish congregation where her father, a menswear salesman and World War I veteran, was the treasurer. Charlotte remembers having a happy childhood.

This began to change when the Nazi Party came to power in 1933. Hitler Youth paraded down the street, singing songs, and some Jewish students in Aschaffenburg were attacked. The ideals of the Nazi Party began to invade everyday life.

It wasn’t until the arrest of Charlotte’s father in 1936, however , that her happy childhood screeched to a halt. After the Nazi Party sent notice that all synagogue funds would be confiscated, Charlotte’s father distributed all of the money to the poorest members of the congregation and burned the books. The incident, and his subsequent arrest, convinced him that the time for Jews to live in Germany had ended.

While her father looked for a sponsor so they could immigrate to the United States, Charlotte and her sister were sent to the Esslingen Jewish Orphanage, run by a family friend. Very frightened, she realized that there are some things even parents do not have control over: “I had to take care of myself; I realized I am the only person who is always going to be with me.”

In 1938, the family secured sponsorship from a relative that had earlier immigrated to the U.S. On their way to leave the country, they stopped in Koblenz to see her grandfather. On the night of November 9th, their grandfather’s home was vandalized in what would later be known as Kristallnacht. While reporting this crime to the police, her father was arrested again. He was released when he showed proof they were leaving the country.

On December 25th, 1938, Charlotte and her family arrived in New York, where she spent the rest of her childhood. She raised three sons with her first husband Harry Sprung and second husband Norbert Wollheim (the two were also Holocaust survivors who had met in Auschwitz). In 1988 Charlotte met Holocaust educator Vladka Meed and became her assistant. They organized summer trips to Poland for teachers to learn about the Holocaust. In 2000, Charlotte moved to Seattle to be closer to her son Jeff. She now volunteers to read with elementary school children, and is an active member of the Holocaust Center Speakers Bureau.