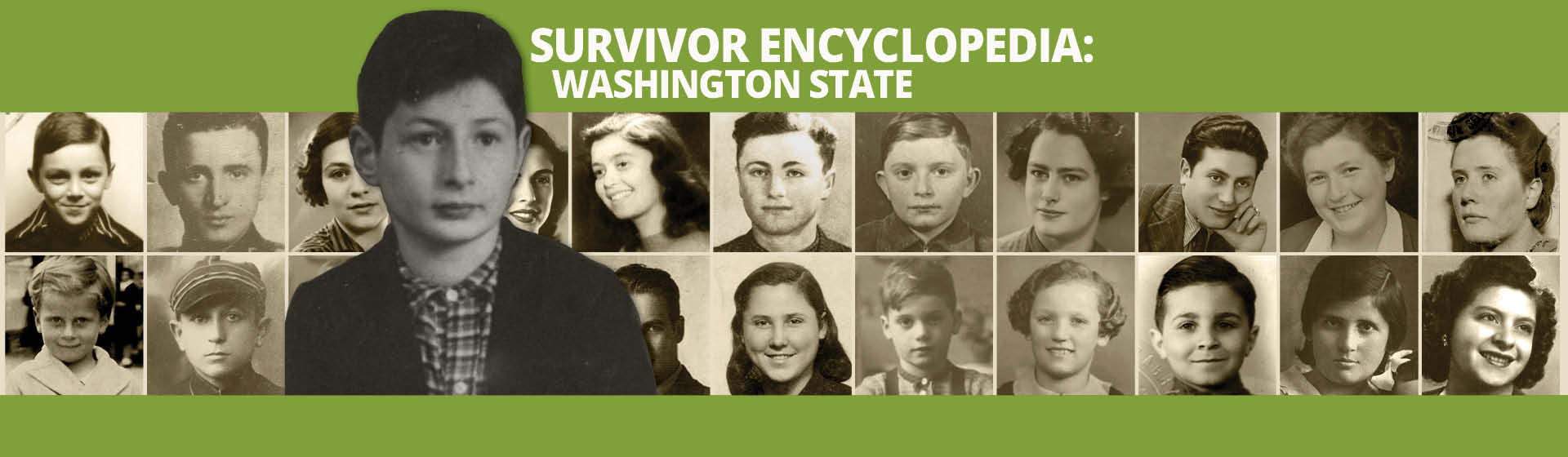

Harriet Mendels was born in the Netherlands to a large Jewish family that was assimilated into Dutch society. Harriet and her brother spent their childhood in the seaside town of Scheveningen, Holland.

Harriet Mendels was born in the Netherlands to a large Jewish family that was assimilated into Dutch society. Harriet and her brother spent their childhood in the seaside town of Scheveningen, Holland.

Her grandfather Pierre, a journalist, traveled through Germany for business in the late 1930s and witnessed the rise and adoption of Nazism along with its antisemitic propaganda. He warned his daughter and son-in-law of the impending danger, urging them to leave Holland while there was still time. Reluctantly, they decided to follow his advice.

The Mendels family – Harriet and her parents, brother, and two aunts – were able to get exit visas from Holland. They also contacted a distant relative in the United States who provided an affidavit of sponsorship for the family. They left Holland and arrived in Hoboken, New Jersey, in May 1939.

Harriet grew up in New York, learning English and adjusting to a new life far from her home country. She was always aware that she was Jewish and occasionally encountered antisemitism in the United States.

Harriet is a mother and grandmother and has been a teacher, activist, local politician, and author. In 2018, aware of rising Holocaust denial, she decided to tell her story, and worked with the Holocaust Center to research her family history more in depth to become a member of the Center’s Speakers Bureau.

The daughter of two survivors, Naomi tells the stories of her parents from primary source documents and historical records.

Naomi is the daughter of two Holocaust survivors. She tells the stories of both of her parents with details from primary source documents and historical records. Their survival is truly remarkable.

In 1938, Naomi’s father Eric Weiss, attended a rally in Vienna after the Germans occupied Austria. He sensed that he had to get his parents out of Vienna and escape himself. He arranged for his parents to take an Eastern escape route through Russia to Yokahama, Japan and finall y to Portland, Oregon. Eric’s acceptance to the Hebrew University allowed him to leave Germany for what was then Palestine under British rule (now Israel). While in Palestine, Eric was recruited to work for as a spy for the British and traveled to Egypt, Algiers, Tunisia, Libya, and Italy in that capacity. He served from 1939-1944.

Naomi’s mother, Gerda Feldmann, was born in 1923 in a small town in what is now the Czech Republic. The Germans invaded Czechoslovakia in 1939 when Gerda was 16. She was sent to a series of slave labor camps in Poland and was finally liberated by British forces at Bergen-Belsen. Gerda, ill with typhus, was sent by the Red Cross to Sweden to recuperate, and eventually she too arrived in Palestine.

Gerda and Eric met in Israel, but Eric left in 1950, traveling to Portland to reunite with his parents. Gerda followed and they were married in 1950. Naomi grew up in Portland hearing parts of these stories. Her mother died when Naomi was 17, but her father lived to be 100.

Naomi calls her story, “Resilience: My Family Story .” She gathered all the documents and pictures she could find, consulted with relatives, and researched many details of this story. Her hope, as one of the Holocaust Center’s Legacy Speakers, is to reach young people and help them to understand the way our lives can be threatened, and what each one of us can do to make a difference.

Steve Pruzan's grandparents and his mother fled Germany in 1939, and made their home in the United States.

Steve Pruzan’s grandparents, Max and Helene Schlonau, owned a large farm in Germany. They had owned and operated the farm at Warmsen, Germany for many generations. It was a gathering place for family who lived nearby. His grandfather, Max Schlonau served in World War I. He studied agriculture, enlarged his land holdings, used the most updated agricultural methods, and invented a breeding method for cattle. He was a leader in the area and in the small Jewish community in Warmsen.

Max and Helene married in 1923 and Steve’s mother, Inge was born in 1924. After 1933, when Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, things got progressively more difficult for the Schlonaus. Inge had to take a 5 hour train ride to Hanover in order to go to school as Jewish students were not allowed in German schools. Max was arrested on Kristallnacht and held at Buchenwald Concentration Camp for 3 weeks until his wife paid a fine to get him released.

By 1938 they had made plans to leave Germany. Helene had a cousin who was already settled in Seattle, Dr. Hans Lehmann. Lehman provided the Schlonau’s with an affidavit, and with Max’s agriculture experience, the family was able to expedite the visa process. They sailed from the Netherlands on September 1, 1939. The Schlonaus settled in Seattle where Dr. Lehmann was a prominent physician.

Steve’s mother, Inge attended Seattle University and graduated with a degree in nursing. She married Howard Pruzan, a Seattle attorney.

Steve is a practicing attorney in Seattle. He shares his family’s story as a member of the Speakers Bureau.

Jack Schaloum is the son of Holocaust survivor Magda Schaloum, a Hungarian survivor of Auschwitz and other concentration camps.

Jack Schaloum is the son of Holocaust survivor Magda Schaloum, a Hungarian survivor of Auschwitz and other concentration camps.

Magda was born to a loving family in 1922 in Gyor, Hungary. Following the German occupation of Hungary on March 19, 1944, the Nazis began systematicall y depriving Jews of their rights and forcing them into ghettos. They forced Magda and her family to leave their home and deported Magda, her brother and mother to Auschwitz.

Through the window of the cattle car, Magda saw her father desperately trying to give them a package filled with food and essentials. The SS guards treated him brutally, but took the package and told him they would give it to his family. Instead, the SS guards kept it for themselves. Magda’s father was held for forced labor in the coal mines, and the Nazis eventually transported him to the Buchenwald slave labor camp in Germany. Magda’s sister avoided deportation thanks to one of the protective papers from the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, later declared a Righteous Among the Nations.

After riding for days in the fetid cattle car, Magda arrived in Auschwitz, only to be separated from her brother, 15, and her mother, 56. The Nazis forced Magda to processing where they tattooed a number on her arm.

At Mühldorf, (another slave labor camp) in April, 1945, Magda met the man she would eventually marry: Mr. Izak Schaloum, a Sephardic native of Salonika, Greece. Their stay at Mühldorf was brief. The Nazis loaded them onto a cattle wagon with other survivors to be transported to an unknown spot to be murdered, but Allied troops liberated them along the way.

Magda passed away in June 2015. Her son Jack is a member of the Holocaust Center for Humanity's Speakers Bureau and is carrying on his mother’s legacy by sharing her story.

To learn about Magda's story, visit the Survivor Encyclopedia.